The history of naturalistic textual criticism

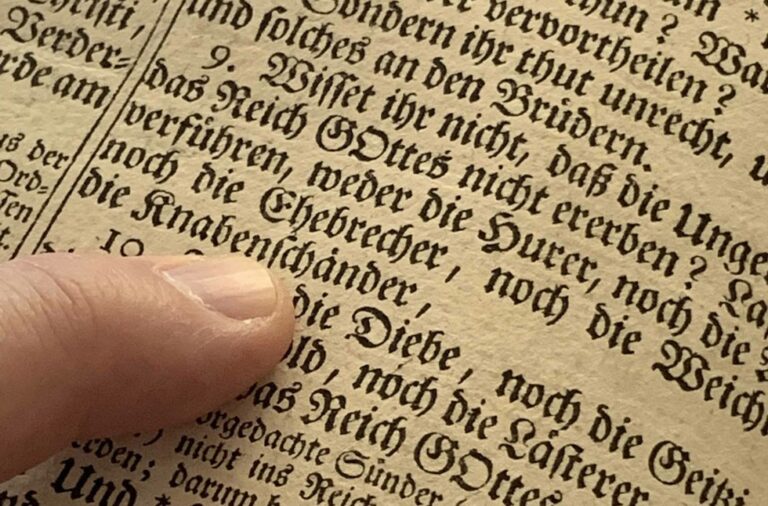

The KJV is based on a Greek New Testament text called the Textus Receptus, first published by Desiderius Erasmus in 1516 and subsequently revised by a number of scholars. Most modern translations are based on the Nestle-Aland/United Bible Society (NA/UBS) text, published by the Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft (German Bible Society). In the past half-century, the NA/UBS text has become the most widely accepted Greek New Testament among textual scholars and Bible societies. Accordingly, many evangelical leaders now promote and prefer the NA/UBS text. The NA/UBS text is hailed as the more “scholarly” and “accepted” edition. However, the “scholarship” underlying the NA/UBS text can be demonstrated to be a product of liberal (rather than evangelical) theology and methodology, and that its wide “acceptation” is due to an official agreement between the United Bible Societies and the Roman Catholic Church.

The editors of the NA/UBS text severely criticized the Textus Receptus, going as far as characterizing the Textus Receptus as the “poorest form of the New Testament text”. The introduction to the Nestle-Aland 26th edition says:

“When Eberhard Nestle produced the first edition of the Novum Testamentum Graece in 1898, neither he nor the sponsoring Wurttemburg Bible Society could have imagined the full extent of what had been started. Although the Textus Receptus could still claim a wide range of defenders, the scholarship of the nineteenth century had conclusively demonstrated it to be the poorest form of the New Testament text.” (Introduction to Novum Testamentum Graece – Nestle-Aland 26th Edition)

This introduction fails to describe what is meant by “the scholarship of the nineteenth century”. The scholarship that is referred to here is not evangelical scholarship, but rather liberal scholarship. Unfortunately, many evangelical Christians fail to examine further as to what kind of scholarship is meant here and fail to see that theology and one’s worldview heavily affect the decisions that go into textual criticism.

The Textus Receptus was based on the scholarship of Christians who believed in the truths of scripture. The Textus Receptus was first edited in 1516 by the Catholic Reformer Desiderius Erasmus who sought to correct the abuses of the Catholic Church from within. When the Reformation was in full swing after 1517, the Textus Receptus underwent several revisions under the hands of godly Protestant men, such as Robert Stephanus, the distinguished printer of Protestant literature, and Theodore Beza, the successor of John Calvin. The Greek New Testament put forward to the world by these men became the standard New Testament text of Bible-believing Christians for nearly five centuries. This was the time of great Christian revivals spanning from the Reformation to the Victorian era, a time referred to by some Christians as the Philadelphian age of Church history (Revelation 3:7-12). This was a time when Christians had full assurance that the Word of God was “profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for correction, for instruction in righteousness: That the man of God may be perfect, throughly furnished unto all good works” (2 Timothy 3:16-17). This era in history saw the unprecedented growth of the Bible-believing Church.

Since about the time of the Victorian era, however, the Christian world saw a sweeping tide of liberalism and apostasy. One of the damaging legacies of liberalism which made its way into evangelical Christianity was the “outsourcing” of academic disciplines to non-evangelicals. Evangelicals continued to formulate their own doctrines on soteriology, eschatology, etc., but they left many other inquiries in the hands of non-evangelicals. For example, Christians outsourced the study of science to atheists and non-evangelicals. Until the rise of the modern creationist and intelligent design movements, Christians naively accepted the scientific theories on origins proposed by non-evangelicals. This same outsourcing occurred in archeology, psychology and in many other academic fields. The outsourcing of biblical textual criticism began around the same time in the late 19th century.

Westcott/Hort Greek New Testament published in 1881

Eighteenth century German textual scholars, Johann Griesbach and Johann Bengel, spurred the modern textual critical theory of re-examining the Textus Receptus and introduced a number of “scientific” criteria for determining authentic New Testament readings. In the late nineteenth century, English Churchmen Brooke Westcott and Fenton Hort adopted many of these criteria. The most influential of these criteria are the following as described by them in The New Testament in the Original Greek, the Text Revised by B.F. Westcott and F.J.A. Hort (Cambridge : MacMillan & Co., 1882):

-

There is a stronger presumption that the earlier date of a manuscript implies “greater purity of text” (p. 59)

-

A reading that is apparently an “improvement” of the text is less likely to be authentic (p. 27)

-

A more difficult reading is to be preferred as scribes tended to “smooth away difficulties” (p. 28)

The establishment of these “scientific” criteria for textual criticism caused the divine work of biblical preservation to become a merely naturalistic enterprise. If the only criteria to determine the authentic readings are to determine what manuscripts are the oldest and what readings are supposedly less “improved” and “smooth”, then where does one’s faith fit in? While the beliefs of the eighteenth and nineteenth century textual critics allegedly still belonged within the bounds of evangelical Protestantism (though this is questionable), their naturalistic textual theories which left no need for spiritual discernment left the door open for non-evangelicals in the next century to usurp the field of textual criticism.

Editors of the Nestle-Aland Greek New Testament

In the course of the twentieth century, textual critics, Kurt Aland, Bruce Metzger, Cardinal Carlo Martini and others built on the works of Brooke Westcott and Fenton Hort and produced what is called the Nestle-Aland or United Bible Society Greek (NA/UBS) text. Metzger wrote:

“The international committee that produced the United Bible Societies Greek New Testament, not only adopted the Westcott and Hort edition as its basic text, but followed their methodology in giving attention to both external and internal consideration” (James Brooks, Bible Interpreters of the 20th century, p. 264).

Today, this NA/UBS text is the standard Greek New Testament text for study in evangelical seminaries and translation by Bible societies. All major evangelical Bible translations printed today, except the King James Version, New King James Version and some others, are based on the NA/UBS text. Many who are taught to use the NA/UBS text are fine evangelical pastors and scholars who are sound in many of their doctrines. Nevertheless, the architects and custodians of the NA/UBS text were theological liberals who did not believe in the traditional Protestant canon and the inerrancy and infallibility thereof.

Kurt Aland is a liberal who doubted the canonicity of the books in the Bible [LINK to article at the Trinitarian Bible Society]. Bruce Meztger likewise shared many liberal views, as evidenced by his direct involvement in the editing of the ecumenical and theologically liberal New Revised Standard Version. Cardinal Carlo Martini is a Jesuit – a Roman Catholic order created to oppose the Reformation [LINK to Wikipedia article]. A twentieth century Jesuit is to be distinguished from a sixteenth century Catholic Reformer such as Erasmus who sought to reform the Catholic Church from within while the future of Protestantism was uncertain. Our evangelical pastors would not dare let the Nestle-Aland editors edit their Sunday school materials, yet they allow these men to edit their New Testament.

Metzger and Ehrman, co-authors of a primer on Textual Criticism

Many evangelical seminarians are assigned or recommended to use Metzger’s book, The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration, as a primer on textual criticism. Perhaps many seminarians are unaware that the 4th edition of the book published in 2005 is co-authored by Metzger and Bart Ehrman (Link to Amazon Books). The name of Ehrman should ring a bell among many Evangelical scholars as he is the same agnostic author who wrote, “Forged: Writing in the Name of God – Why the Bible’s Authors Are Not Who We Think They Are (2011)” and “Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why” (2007).

Men who compiled the Textus Receptus such as Erasmus and Beza, though not perfect in their theology, did not separate providence and ecclesiology from textual criticism. These men understood that God gave his Church the authority and the responsibility to preserve the New Testament text and that the tools used to identify the true text were faith in God’s intervention and spiritual discernment, not just intellectual expertise. Proponents of the new modern textual criticism, however, separated the spiritual from the intellectual and made textual criticism into a merely academic enterprise. This was a grave mistake as the separation of the spiritual from the intellectual in textual criticism led to Bible-believing Christians outsourcing textual criticism to whomever that seemed to have the academic credentials, regardless of that textual critic’s faith, theology and worldview.

The NA/UBS text is not a product of biblical Christianity

The United Bible Societies, the promoters of this NA/UBS text, is an ecumenical umbrella society of national Bible societies which are also ecumenical in purpose and membership. The British and Foreign Bible Society, a member of the United Bible Societies, was the first Bible society to publish and distribute English Bibles. However, by 1831, the Society had admitted professing Unitarians in important positions. Unitarians do not believe that Jesus Christ is God himself. Members who became concerned with the increasing involvement of Unitarians in the Society separated to form the Trinitarian Bible Society (The Official History can be viewed on their website). The Trinitarian Bible Society continues to this day to publish the Textus Receptus, but the British and Foreign Bible Society, and hence the United Bible Societies, abandoned the Textus Receptus in the late 19th century. The Trinitarian Bible Society is much smaller and less influential than the United Bible Societies, which has the backing of the Vatican. The Introduction to the Nestle-Aland: Novum Testamentum Graece, 27th revised edition (2006) explicitly confirms this close relationship between the UBS and the Vatican:

“The text shared by these two editions was adopted internationally by Bible Societies, an following an agreement between the Vatican and the United Bible Societies it has served as the basis for new translations and for revisions made under their supervision. This marks a significant step with regard to interconfessional relationships.” (p. 45)

When Pope Francis was elected in 2013, the United Bible Societies praised the new Pope with open arms and affirmed the UBS’s close collaboration with the Vatican. UBS General Secretary Michael Perreau stated:

“As a long-time friend of the Bible Societies Pope Francis knows that our raison d’être is the call to collaborate in the incarnation of our Christian faith…. We assure Pope Francis of our renewed availability to serve the Catholic Church in her endeavours to make the Word of God the centre of new evangelisation.” (Webpage: United Bible Societies welcomes Pope Francis)

The reason the NA/UBS text is widely accepted is because it is the standard text of the large and influential Roman Catholic Church.

It is undeniable that the men behind the Textus Receptus were Bible-believers whereas the men behind the NA/UBS text were theological liberals. In making this comparison, one should not assume that a theological liberal would act dishonestly or carelessly in editing a text. However, a Bible-believer and a theological liberal approach the biblical text with very different viewpoints and assumptions. As textual criticism is not an exact science, there are many times when the evidence is divided and either choice may seem reasonable from a naturalistic perspective. The following words of Hort should make us wary of a text that is compiled by theological liberals and Jesuits:

“The first impulse in dealing with a variation is usually to lean on Intrinsic Probability, that is, to consider which of two readings makes the best sense, and to decide between them accordingly. The decision may be made either by an immediate and as it were intuitive judgment, or by weighing cautiously various elements which go to make up what is called sense, such as conformity to grammar and congruity to the purport of the rest of the sentence and of the larger context; to which may rightly be added congruity to the usual style of the author and to his matter in other passages. (The New Testament in the Original Greek, the Text Revised by B.F. Westcott and F.J.A. Hort (Cambridge : MacMillan & Co., 1882), p. 20)”

Should Evangelicals use a text that may have been based on the “intuitive judgment” of theological liberals and Jesuits? Should Evangelicals use a text with readings made congruous with the “usual style of the author” when the editing theological liberal may not even believe that the author is who is stated to be? As textual criticism requires the exercise of discretion, it is impossible to discern the correct reading without the “mind of Christ”. 1 Corinthians 2:14-16 says,

“But the natural man receiveth not the things of the Spirit of God: for they are foolishness unto him: neither can he know them, because they are spiritually discerned. But he that is spiritual judgeth all things, yet he himself is judged of no man. For who hath known the mind of the Lord, that he may instruct him? But we have the mind of Christ.”

The Bible is the word of God. Only his sheep can hear his voice through his word. Our Lord said, “My sheep hear my voice” (John 10:27). Since textual criticism is the art of discerning whether a reading is God’s voice or not, the Church must not delegate this deeply spiritual exercise to theological liberals. Evangelicals ought to be more discerning and reclaim the biblical mandate to be its own custodian of the inspired, infallible and inerrant preserved words of God.